文档内容

TESTFOR ENGLISHMAJORS(2012)

-GRADE EIGHT-

TIMELIMIT:115MIN

PARTⅠ LISTENINGCOMPREHENSION(25MIN)

SECTIONA MINI-LECTURE

Inthis sectionyouwillhearamini-lecture.Youwillhearthe mini-lecture ONCEONLY.Whilelisteningto

the mini-lecture, please complete the gap-filling task on ANSWER SHEET ONE and write NO MORE THAN

THREE WORDS for each gap. Make sure the word (s) you fill in is(are) both grammatically and semantically

acceptable.Youmayusetheblanksheetfornote-taking.

YouhaveTHIRTYsecondstopreviewthegap-fillingtask.

Nowlistentothemini-lecture.Whenitisover,youwillbegivenTHREEminutestocheckyourwork.

SECTIONB INTERVIEW

In this section you will hear ONE interview. The interview will be divided into TWO parts. At the end of

each part, five questions will be asked about what was said. Both the interview and the questions will be spoken

ONCE ONLY.After each question there will be a ten-second pause. During the pause, you should read the four

choicesof[A],[B],[C],and[D],andmarkthebestanswertoeachquestiononANSWERSHEETTWO.

YouhaveTHIRTYsecondstopreviewthechoices.

Now,listentoPartOneoftheinterview.

1.[A]Thecreativityofgiftedpeople. [B]Thebrainbehindcreativity.

[C]Towtobecreative. [D]Whatiscreativity.

2.[A]Creativitystemsfromhumanbeings’novelthinking.

[B]Thedurationofthecreativeprocessvariesfrompersontoperson.

[C]Creativepeoplefocusonnovelthinkingratherthanonsolutions.

[D]Theoutcomeofhumancreativitycomesinvariedforms.

3.[A]Manyyears. [B]Afewhours.

[C]Itgoesbyinaflash. [D]Itdepends.

4.[A]Toshowthatcreativityappearstobetheresultoftheenvironment.

[B]Toshowthatcreativityseemstobeattributabletogeneticmakeup.

[C]Toshowthatcreativityappearstobemoreassociatedwithgreatpeople.

[D]Toshowthatcreativitycomesfrombothenvironmentandgeneticmakeup.

5.[A]Ordinarypeoplecanalsobecreative.

[B]Onlygreatpeoplecanproducegreatpieces.

[C]Thatacookchangestherecipeisnotaprocessofcreativity.

[D]Thefamouspeoplearemorecreative.

Mow,listentoPartTwooftheinterview.

6.[A]One. [B]Two. [C]Three. [D]Four.

7.[A]Unconventional. [B]Original. [C]Resolute. [D]Critical.

8.[A]Brainexercisingwillnotmakepeoplecreative.

[B]Mostpeoplehavediversifiedinterestsandhobbies.

[C]Theenvironmentissignificantinthecreativeprocess.

[D]Creativitycanonlybefoundingreatpeople.

9.[A]13minutesaday. [B]20minutesaday.

[C]30minutesaday. [D]1houraday.

10.[A]Exploreanunfamiliarareaofknowledge. [B]Spendtimethinkingeveryday.

[C]Practicetheartofpayingattention. [D]Observeanobjecteveryday.PART Ⅱ READING COMPREHENSION(45MIN)

SECTIONA MULTIPLE-CHOICEQUESTIONS

Inthis section there areseveralpassages followed byfourteen multiple choice questions. For eachmultiple

choicequestion,therearefoursuggestedanswersmarked[A],[B],[C]and[D].Choosethe onethatyouthinkis

thebestanswerandmarkyouranswersonANSWERSHEETTWO.

PASSAGEONE

I usedto look atmy closet andsee clothes.These days, whenever Icastmy eyes uponthe stacks ofshoes and

hangersofshirts,sweatersandjackets,Iseewater.

It takes 569 gallons to manufacture a T-shirt, from its start in the cotton fields to its appearance on store

shelves.Apairofrunningshoes?1,247gallons.

Until last fall, I’d been oblivious to my “water footprint”, which is defined as the total volume of freshwater

that is used to produce goods and services, according to the Water Footprint Network. The Dutch nonprofit has

been working to raise awareness of freshwater scarcity since 2008, but it was through the “Green Blue Book” by

ThomasM.KostigenthatIwasabletoseehowmyownactionsfactoredin.

I’ve installedgray-watersystems toreusethewastewaterfrommylaundry,machineandbathtubandrerouteit

tomylandscape—systemsthatsave,onaverage,50gallonsofwaterperday.I’vesetuprainbarrelsandinfiltration

pits to collect thousands of gallons of storm water cascading from my roof. I’ve even entered the last bastion of

greendom—installingacompostingtoilet.

Suffice to say, I’ve been feeling pretty satisfied with myself for all the drinking water I’ve saved with these

big-ticketprojects.

NowIrealizethatmydailyconsumptionchoicescouldhaveanevenlargereffect—notonlyonthelocalwater

supply but also globally: 1.1 billion people have no access to freshwater, and, in the future, those who do have

accesswillhavelessofit.

Tosee how much virtual water I was using, I logged on to the “Green Blue Book” website and used its water

footprint calculator, entering my daily consumption habits. Tallying up the water footprint of my breakfast, lunch,

dinner and snacks, as well as my daily dose of over-the-counter uppers and downers—coffee, wine and beer—I’m

using512gallonsofvirtualwatereachdayjusttofeedmyself.

Inaword:alarming.

EvenmorealarmingwashowmuchhiddenwaterIwasusingtogetdressed.I’mhardlyaclotheshorse,butthe

few new items I buy once again trumped the amount of water flowing from my faucets each day. If I’m serious

about saving water, I realized I could make some simple lifestyle shifts. Looking more closely at the areas in my

life that use the most virtual water, it was food and clothes, specifically meat, coffee and, oddly, blue jeans and

leatherjackets.

Being a motorcyclist, I own an unusually large amount of leather - boots and jackets in particular.All of it is

enormously water intensive. It takes 7,996 gallons to make a leather.jacket, leather being a byproduct of beef. It

takes2,866gallonsofwatertomakeasinglepairofbluejeans,becausethey’remadefromwater-hoggingcotton.

Crunching the numbers for the amount of clothes I buy every year, it looks a lot like my friend’s swimming

pool.MyentireclosetisborderlineOlympic.

Gulp.

My late resolution is to buy some items used. Underwear and socks are, of course, exempt from this strategy,

butIhave no problemshoppingless andalso shoppingatGoodwill. In fact, I’d beendoingthatfor the pastyear to

savemoney.Myclothes’outrageouswaterfootprintjustfeinforceditforme.

More conscious living and substitution, rather than sacrifice, are the prevailing ideas with the water footprint.

It’soneI’mtrying, andthat’shadanunusualupside.Ihadahamburgerrecently,andIenjoyeditalotmoresinceit

isnowanoccasionaltreatratherthanaweeklyhabit.(Onegallon=3.8litres)

11.Accordingtothepassage,theWaterFootprintNetwork________.

[A]madetheauthorawareoffreshwatershortage.[B]helpedtheauthorgettoknowtheGreenBlueBook

[C]workedforfreshwaterconservationfornonprofitpurposes

[D]collaboratedwiththeGreenBlueBookinfreshwaterconservation

12.Whichofthefollowingreasonscanbestexplaintheauthorsfeelingofself-satisfaction?

[A]Hemadecontributiontodrinkingwaterconservationinhisownway.

[B]Moneyspentonupgradinghishouseholdfacilitieswasworthwhile.

[C]Hishousewasequippedwithadvancedwater-savingfacilities.

[D]Hecouldhavemadeevengreatercontributionbychanginghislifestyle.

13.Accordingtothecontext,“...howmyownactionsfactoredin”means

[A]howIcouldcontributetowaterconservation

[B]whateffortsIshouldmaketosavefreshwater

[C]whatbehaviourcouldbecountedasfreshwater-saving

[D]howmuchofwhatIdidcontributedtofreshwatershortage

14.Whatisthetoneoftheauthorinthelastparagraph?

[A]Sarcastic. [B]Ironic. [C]Critical. [D]Humorous.

PASSAGETWO

In her novel of “Reunion, American Style”, Rona Jaffe suggests that a class reunion “is more than a

sentimentaljourney.Itisalsoawayofansweringthequestionthatliesatthebackofnearlyallourminds.Didthey

dobetterthanI?”

Jaffe’s observation may be misplaced but not completely lost. According to a study conducted by social

psychologist Jack Sparacino, the overwhelming majority who attend reunions aren’t there invidiously to compare

their recent accomplishments with those of their former classmates. Instead, they hope, primarily, to relive their

earliersuccesses.

Certainly, a few return to show their former classmates how well they have done; others enjoy observing the

changes that have occurred in their classmates (not always in themselves, of course). But the majority who attend

their class reunions do so to relive the good times they remember having when they were younger. In his study,

Sparacino found that, as high school students, attendees had been more popular, more often regarded as attractive,

andmoreinvolvedinextracurricularactivities thanthoseclassmateswhochosenottoattend.Forthosewhoturned

upattheirreunions,then,theoldtimeswerealsothegoodtimes!

It would appear that Americans have a special fondness for reunions, judging by their prevalence. Major

league baseball players, fraternity members, veterans groups, high school and college graduates, and former Boy

Scouts all hold reunions on a regular basis. In addition, family reunions frequently attract blood relatives from

farawayplaceswhospendconsiderablemoneyandtimetoreunite.

Actually, in their affection for reuniting with friends, family or colleagues, Americans are probably no

different from any other people, except that Americans have created a mind-boggling number and variety of

institutionalized forms of gatherings to facilitate the satisfaction of this desire. Indeed, reunions have increasingly

becomeformaleventsthatareorganizedonaregularbasisand,intheprocess,theyhavealsobecomebigbusiness.

Shell Norris of Class Reunion, Inc., says that Chicago alone has 1,500 high school reunions each year. A

conservative estimate on the national level would be 10,000 annually.At one time, all high school reunions were

organized by volunteers, usually female homemakers. In the last few years, however, as more and more women

haveenteredthelabourforce,alumnireunionsareincreasingly beingplannedbyspecialized companiesratherthan

bypart-timevolunteers.

The first college reunion was held by the alumni of Yale University in 1792. Graduates of Pennsylvania,

Princeton, Stanford, and Brown followed suit. And by the end of the 19th century, most 4-year institutions were

holdingalumnireunions.

The variety of college reunions is impressive. At Princeton, alumni parade through the town wearing their

class uniforms and singing their alma mater. At Marietta College, they gather for a dinner-dance on a steamshipcruisingtheOhioRiver.

Clearly, the thought of cruising on a steamship or marching through the streets is usually not, by itself,

sufficientreasonforlargenumbersofalumnitoreturntocampus.Alumniwhodecidetoattendtheirreunionsshare

a common identity based on the years they spent together as undergraduates. For this reason, universities that

somehowestablishacommonbond–forexample,becausetheyarerelativelysmallorespeciallyprestigious—tend

to draw substantial numbers of their alumni to reunions. In an effort to enhance this common identity, larger

colleges and universities frequently build their class reunionson participation in smaller units, suchas departments

or schools. Or they encourage “affinity reunions” for groups of former cheerleaders, editors, fraternity members,

musicians,membersofmilitaryorganizationsoncampus,andthelike.

Of course, not every alumnus is fond of his or her alma mater. Students who graduated during the late 1960s

maybeespeciallyreluctanttogetinvolvedinalumnievents.Theywerepartofthegenerationthatconductedsit-ins

and teach-ins directed at university administrators, protested military recruitment on campus and marched against

“establishment politics.” If this generation has a common identity, it may fall outside of their university ties—or

evenbehostiletothem.Evenastheyentertheirmiddleyears,alumniwhocontinuetoholdunpleasantmemoriesof

collegeduringthisperiodmaynotwishtoattendclassreunions.

15.Accordingtothepassage,Sparacino’sstudy________.

[A]providedstrongevidenceforJaffe’sstatement

[B]showedthatattendeestendedtoexcelinhighschoolstudy

[C]foundthatinterestinreunionswaslinkedwithschoolexperience

[D]foundevidenceforattendeesintensedesireforshowingoffsuccess

16.WhichofthefollowingisNOTmentionedasadistinctfeatureofU.S.classreunions?

[A]U.S.classreunionsareusuallyoccasionstoshowoffonesrecentsuccess.

[B]Reunionsareregularandformaleventsorganizedbyprofessionalagencies.

[C]Classreunionshavebecomeaprofitablebusiness.

[D]Classreunionshavebroughtaboutavarietyofactivities.

17.Therhetoricalfunctionofthefirstparagraphisto________.

[A]introduceRonaJeffe’snovel [B]presenttheauthor’scounterargument

[C]serveaspreludetotheauthor’sargument [D]bringintofocuscontrastingopinions

18.Whatisthepassagemainlyabout?

[A]Reasonsforpopularityand(non)attendanceforalumnireunions.

[B]AhistoricalperspectiveforalumnireunionsintheUnitedStates.

[C]AlumnireunionsandAmericanuniversitytraditions.

[D]Alumnireunionanditssocialandeconomicimplications.

PASSAGETHREE

Onetime while onhis walkGeorge metMr.Cattanzara cominghome very latefrom work. He wonderedif he

was drunkbutthen couldtell he wasn’t. Mr.Cattanzara, a stocky,bald-headedman who worked in a change booth

onan IRTstation, lived on the next blockafter George’s, above a shoe repair store. Nights, during the hotweather,

hesat onhis stoopin an undershirt, reading the New YorkTimesin thelight of theshoemaker’s window.He readit

from the first page to the last, then went up to sleep. And all the time he was reading the paper, his wife, a fat

woman with a white face, leaned out of the window, gazing into the street, her thick white arms folded under her

loosebreast,onthewindowledge.

Once in a while Mr. Cattanzara came home drunk, but it was a quiet drunk. He never made any trouble, only

walkedstifflyupthestreetandslowlyclimbedthestairs intothe hall.Thoughdrunkhelooked thesame asalways,

except for his tight walk, the quietness, and that his eyes were wet. George liked Mr. Cattanzara because he

remembered him giving him nickels to buy lemon ice with when he was a squirt. Mr. Cattanzara was a different

typethanthoseintheneighbourhood.Heaskeddifferentquestionsthantheotherswhenhemetyou,andheseemed

toknowwhatwentoninallthenewspapers.Hereadthem,ashisfatsickwifewatchedfromthewindow.“What are you doingwith yourself this summer,George?” Mr.Cattanzara asked. “I see you walkin’aroundat

night.”

Georgefeltembarrassed.“Iliketowalk.”

“Whatareyoudoin’inthedaynow?”

“Nothingmuchjustnow.I’m waitingforajob.”Since itshamedhimtoadmit thathewasn’tworking, George

said,“I’mreadingalottopickupmyeducation.”

“Whatareyoureadin’?”

George hesitated, then said, “I got a list of books in the library once and now I’m gonna read them this

summer.”Hefeltstrangeandalittleunhappysayingthis,buthewantedMr.Cattanzaratorespecthim.

“Howmanybooksarethereonit?”

“Inevercountedthem.Maybearoundahundred.”

Mr.Cattanzarawhistledthroughhisteeth.

“I figure if I did that,” George went on earnestly, “it would help me in my education. I don’t mean the kind

theygiveyouinhighschool.Iwanttoknowdifferentthingsthantheylearnthere,ifyouknowwhatImean.”

Thechangemakernodded.“Stillandall,onehundredbooksisaprettybigloadforonesummer.”

“Itmighttakelonger.”

“Afteryou’refinishedwithsome,maybeyouandIcanshootthebreezeaboutthem?”saidMr.Cattanzara.

“WhenI’mfinished,”Georgeanswered.

Mr. Cattanzara went home and George continued on his walk. After that, though he had the urge to, George

did nothing different from usual. He still took his walks at night, ending up in the little park. But one evening the

shoemakeronthenextblockstoppedGeorgetosayhewasagoodboy,andGeorgefiguredthatMr.Cattanzarahad

told him all about the books he was reading. From the shoemaker it must have gone down the street, because

Georgesawacoupleofpeoplesmilingkindlyathim,thoughnobodyspoketo himpersonally.He feltalittle better

aroundthe neighbourhood and liked it more, though notso much he would wantto live in it forever.He had never

exactlydislikedthepeopleinit,yethehadneverlikedthemverymucheither.Itwasthefaultoftheneighbourhood.

To his surprise, George found out that his father and his sister Sophie knew about his reading too. His father was

tooshytosayanythingaboutit—hewasnevermuchofatalkerinhiswholelife—butSophiewassoftertoGeorge,

andsheshowedhiminotherwaysshewasproudofhim.

19.Intheexcerpt,Mr.Cattanzarawasdescribedasamanwho________.

[A]wasfondofdrinking [B]showedawideinterest

[C]oftenworkedovertime [D]likedtogossipafterwork

20.Itcanbeinferredfromthepassagethat________.

[A]Mr.CattanzarawassurprisedatGeorge’sreadingplan

[B]Mr.CannazarawasdoubtfulaboutGeorgethroughout

[C]Georgewasforcedtotellalieandthenregretted

[D]Georgeliedatthebeginningandthenbecameserious

21.WecantellfromtheexcerptthatGeorge________.

[A]hadaneitherclosenordistantrelationshipwithhisfather.

[B]wasdissatisfiedwithhislifeandsurroundings

[C]foundthathissisterremainedskepticalabouthim

[D]foundhisneighbourslikedtopoketheirnoseintohim

PASSAGEFOUR

Abraham Lincoln turns 200 this year, and he’s beginning to show his age. When his birthday arrives, on

February12,Congress willholdaspecialjointsessionintheCapitol’sNationalStatuaryHall, awreathwillbelaid

at the great memorial in Washington, and a webcast will link school classrooms for a “teach-in” honouring his

memory.

Admirable as they are, though, the events will strike many of us Lincoln fans as inadequate, even halfhearted—and another sign that our appreciation for the 16th president and his towering achievements is slipping away.

Andyoudon’thavetobeaLincolnenthusiasttobelievethatthisissomethingwecantaffordtolose.

Compare this year’s celebration with the Lincoln centennial, in 1909. That year, Lincolns likeness made its

debutonthepenny,thanks toapprovalfromtheU.S.SecretaryoftheTreasury.Communitiesandcivicassociations

in every comer of the country erupted in parades, concerts, balls, lectures, and military displays. We still feel the

effects today: The momentum unloosed in 1909 led to the Lincoln Memorial, opened in 1922, and the Lincoln

Highway,thefirstpavedtranscontinentalthoroughfare.

The celebrants in 1909 had a few inspirations we lack today. Lincoln’s presidency was still a living memory

forcountlessAmericans.In2009wearefarther intimefromtheendoftheSecondWorldWarthantheywerefrom

theCivilWar;familiesstillfeltthelossoflovedonesfromthatawfulnationaltrauma.

ButAmericans in 1909 had something more: an unembarrassed appreciation for heroes and an acute sense of

thewaythatevenlong-deadhistoricalfigurespressinonthepresentandmakeuswhoweare.

OnestorywillillustratewhatI’mtalkingabout.

In2003agroupoflocalcitizensarrangedtoplaceastatueofLincolninRichmond,Virginia,formercapitalof

the Confederacy. The idea touched off a firestorm of controversy.The Sons of Confederate Veterans held a public

conference of carefully selected scholars to “reassess” the legacy of Lincoln. The verdict—no surprise—was

negative:Lincolnwaslabeledeverythingfromaracisttotalitariantoatellerofdirtyjokes.

I covered the conference as a reporter, but what really unnerved me was a counter-conference of scholars to

refute the earlier one. These scholars drew a picture of Lincoln that only our touchy-feely age could conjure up.

The man who oversaw the most savage war in our history was described—by his admirers, remember—as

“nonjudgmental,”“unmoralistic,”“comfortablewithambiguity.”

I felt the way a friend of mine felt as we later watched the unveiling of the Richmond statue in a subdued

ceremony:“Buthessosmall!”

The statue in Richmond was indeed small; like nearly every Lincoln statue put up in the past half century, it

was life-size and was placed at ground level, a conscious rejection of the heroic—approachable and human, yes,

butnotsomethingtolookupto.

TheRichmondepisodetaughtmethatAmericanshavelostthelanguage toexplainLincoln’sgreatnessevento

ourselves. Earlier generations said they wanted their children to be like Lincoln: principled, kind, compassionate,

resolute.TodaywewantLincolntobelikeus.

ThishelpstoexplainthelongstringofrecentbooksinwhichwritershavepresentedaLincolnmadeaftertheir

own image. We’ve had Lincoln as humorist and Lincoln as manic-depressive, Lincoln the business sage, the

conservativeLincolnandtheliberalLincoln,theemancipatorandtheracist,thestoicphilosopher,theChristian,the

atheist—LincolnovereasyandLincolnscrambled.

What’softenmissing,,though,isthetimelessLincoln,theLincolnwhomallgenerations,ourownnolessthan

that of 1909, can lay claim to. Lucky for us, those memorializers from a century ago—and, through them, Lincoln

himself—have left us a hint of where to find him. The Lincoln Memorial is the most visited of our presidential

monuments. Here is where we find the Lincoln who endures: in the words he left us, defining the country we’ve

inherited.HereistheLincolnwhocanbeendlesslyrenewedandwho,200yearsafterhisbirth,retainsthepowerto

renewus.

22.Intheauthor’sopinion,thecounter-conference________.

[A]rectifiedthejudgmentbythosecarefullyselectedscholars

[B]offeredabrandnewreassessmentperspective

[C]cameupwithsomewhatfavourableconclusions

[D]resultedinsimilardisparagingremarksonLincoln

23.Accordingtotheauthor,theimageofLincolnconceivedbycontemporarypeople________.

[A]conformstotraditionalimages

[B]reflectsthepresent-daytendencyofworship[C]showsthepresent-daydesiretoemulateLincoln

[D]revealsthevarietyofcurrentopinionsonheroes

24.Whichofthefollowingbestexplainstheimplicationofthelastparagraph?

[A]Lincoln’sgreatnessremainsdespitethepassageoftime.

[B]Thememorialissymbolicofthegreatman’sachievements.

[C]EachgenerationhasitowninterpretationofLincoln.

[D]PeoplegettoknowLincolnthroughmemorializers.

SECTIONB SHORT-ANSWERQUESTIONS

In this section there are eight short-answer questions based on the passages in SECTION A. Answer each

questioninNOmorethan10wordsinthespaceprovidedonANSWERSHEETTWO.

PASSAGEONE

25.Accordingtothepassage,whatdoestheauthorthinkismorealarming?

PASSAGETWO

26.Whatmainlyattractsmanypeopletoreturntocampusforreunion?

PASSAGETHREE

27.WhydidGeorgelikeMr.Cattanzara?

28.WhydidGeorgelietoMr.Cattanzaraandsayhewasreading?

29.WhydidGeorgedoafterthestreetconversationwithMr.Cattanzara?

PASSAGEFOUR

30.Whydoestheauthorthinkthatthisyear’scelebrationisinadequateandevenhalfhearted?

31.Accordingtothepassage,whatreallymakesthe1909celebrationsdifferentfromthisyear’s?

32.WhydidearliergenerationswanttheirchildrentobelikeLincoln?

PART Ⅲ LANGUAGE USAGE(15MIN)

The passage contains TEN errors. Each indicated line contains a maximum of ONE error. In each case,

onlyONEwordisinvolved.Youshouldproofreadthepassageandcorrectitinthefollowingway:

Forawrongword, underlinethewrongwordandwritethecorrectoneintheblank

providedattheendoftheline.

Foramissingword, markthepositionofthemissingwordwitha“∧”signandwritethe

wordyoubelievetobemissingintheblankprovidedattheendof

theline.

Foranunnecessaryword, crosstheunnecessarywordwithaslash“/”andputthewordinthe

blankprovidedattheendoftheline.

EXAMPLE

When∧artmuseumwantsanewexhibit, (1)_____an_____

itneverbuysthingsinfinishedformandhangs (2)___n_e_v_e_r___

themonthewall.Whenanaturalhistorymuseum

wantsanexhibition,itmustoftenbuildit. (3)___e_x_h_ib_i_t__

ProofreadthegivenpassageonANSWERSHEETTHREEasinstructed.

PART Ⅳ TRANSLATION(25MIN)

Translate the underlined part of the following text into English. Write your translation on ANSWER

SHEETTHREE.

泊珍到偏远小镇的育幼院把生在那里养到1岁的孩子接回来。但泊珍看他第一眼,仿似一声雷劈头而

来。令她晕头胀脑,这l岁的孩子脸型长得如此熟悉,她心里的第一道声音是,不能带回去!

痛苦纠聚心中,眉心发烫发热,胸口郁闷难展,胃里一股气冲喉而上。院长说这孩子发育迟缓时,她更是心头无绪。她在孩子所待的房里来回踱步,这房里还有其他小孩。整个房间只有一扇窗,窗外树影婆

娑。就让孩子留下来吧,这里有善心的神父和修女,这里将来会扩充为有医疗作用的看护中心,这是留住

孩子最好的地方。这孩子是她的秘密,她将秘密留在这树林掩映的建筑罩。

她将秘密留在心头。

PART Ⅴ WRITING(45MIN)

With the continued growth of the number of native English speaking teachers in China’s English learning

schools, English learning will never be the same for students and teachers. Are native English speaking teachers

better than non-native English speaking teachers? The following are opinions from both sides. Read the excerpts

carefullyandwriteyourresponseinabout300words,inwhichyoushould:

1.summarizebrieflytheopinionsfrombothsides;

2.giveyourcomment.

Marks will be awarded for content relevance, content sufficiency, organization and language quality.

Failuretofollowtheaboveinstructionsmayresultinalossofmarks.

Student

My father came over to this country sixty-five years ago not speaking a word of English. Being a tailor by

trade he was soon working in an all immigrant clothes factory where no one spoke native English and just spoke

their country’s languages. Several months later, he started seeking for jobs elsewhere, but with little English, the

places he wanted to work wouldn’t hire him. Frustrated by the rejection, he decided to learn English. He found a

native English speaking house that was renting a room, moved in and soon it became easier and easier for him to

decipher the words he already knew but had not actually heard spoken before by someone who was a native

English speaker. By being forced to communicate in English, his pronunciation improved and his ears started to

decipher the accents around him. Elated that he could speak more freely, he soon paid for weekly lessons with a

retiredschoolteacherwhowasanativeEnglishspeaker;withinsixmonthsheunderstoodmostofwhatwasspoken

to him, but more importantly his verbal fluency increased. He was able to joke with everyone around him, using

idiomsandpepperinghisspeechwiththecurrentpopreferencesofthetime.

He often said to me how important it was to learn from a native speaker when seeking to speak another

language.Tolookathim chirpingalonginEnglish now,is amazing tome.I learnedbothlanguages frombirth, but

to learn another language in my mid-twenties and be fluent is a feat to me, because I would have had a very hard

time. The trick is to listen to the rhythm of the language around you and adjust your hearing and then practice

loudly;myfatherusedtodoitinfrontofamirror.

Teacher

Ibelieveit’samythopeninginanewwindowthatonlyNESTs(Non-nativeEnglishSpeakingTeachers)can

provide a good language model. What I find troubling is that many in the profession assume language proficiency

tobeequaltobeingagood teacher,trivializingmanyotherimportantfactorssuchasexperience,qualifications and

personality. While proficiency might be a necessity, schools should ensure that both the prospective native and

non-native teachers can provide a clear and intelligible language model. Proficiency by itself should not be treated

asthe decidingfactor thatmakes or breaks a teacher.Successfulteaching is so muchmore!As David Crystal putit

in an interview: “All sorts of people are fluent, but only a tiny proportion of them are sufficiently aware of the

structureofthe language.” So if recruiters careaboutstudents’progress,I suggest taking anobjective andbalanced

viewwhenhiringteachers,andrejectingthenotionthatnativenessusequaltoteachingability.

Most people will agree that language and culture are inextricably connected. But does a “native English

speaker culture” exist? I dare say it doesn’t. After all, English is an official language in more than 60 sovereign

states.EnglishisnotownedbytheEnglishortheAmericans,evenifit’sconvenienttothinkso.ButasHughDellar

notes, even if we look at one country in particular, “there is very clearly no such thing as ‘British culture’in any

monolithic sense.”As native speakers, we shouldhave the humility toacknowledge that“non-nativespeakers have

experience,orunderstandallaspectsoftheculturetowhichtheybelong.”

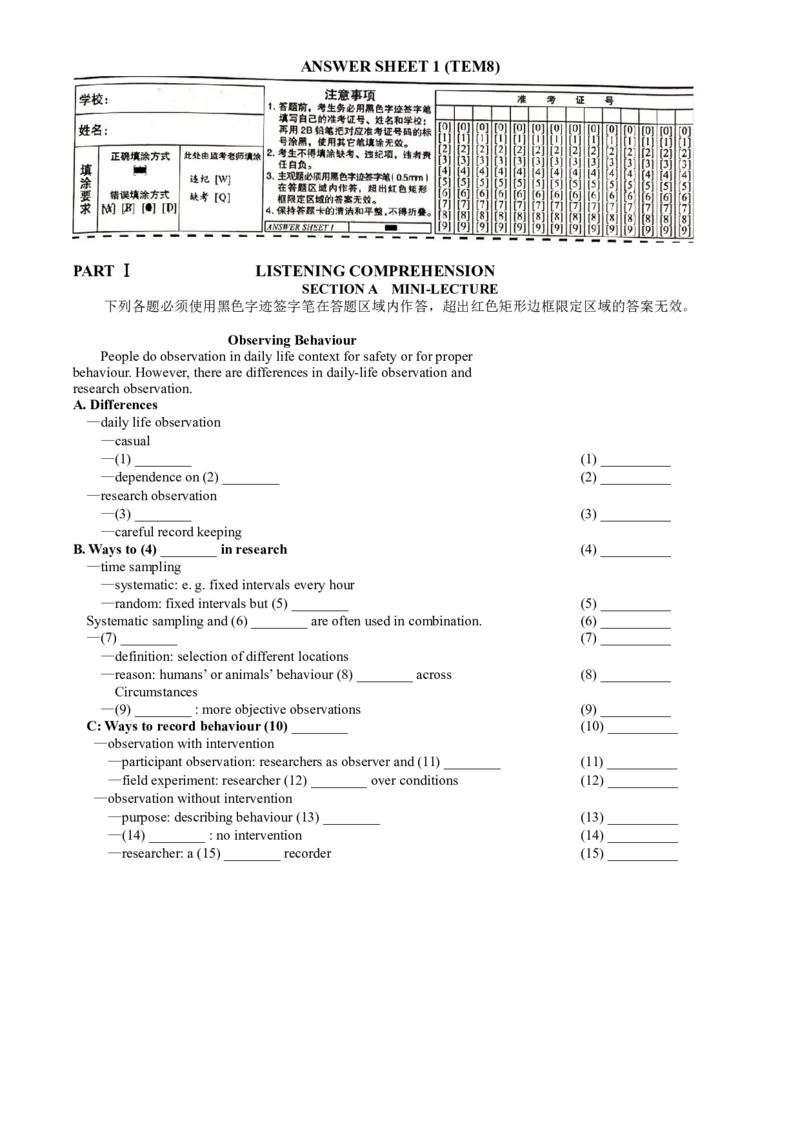

WriteyourresponseonANSWERSHEETFOUR.ANSWERSHEET1(TEM8)

PARTⅠ LISTENINGCOMPREHENSION

SECTIONA MINI-LECTURE

下列各题必须使用黑色字迹签字笔在答题区域内作答,超出红色矩形边框限定区域的答案无效。

ObservingBehaviour

Peopledoobservationindailylifecontextforsafetyorforproper

behaviour.However,therearedifferencesindaily-lifeobservationand

researchobservation.

A.Differences

—dailylifeobservation

—casual

—(1)________ (1)__________

—dependenceon(2)________ (2)__________

—researchobservation

—(3)________ (3)__________

—carefulrecordkeeping

B.Waysto(4)________inresearch (4)__________

—timesampling

—systematic:e.g.fixedintervalseveryhour

—random:fixedintervalsbut(5)________ (5)__________

Systematicsamplingand(6)________areoftenusedincombination. (6)__________

—(7)________ (7)__________

—definition:selectionofdifferentlocations

—reason:humans’oranimals’behaviour(8)________across (8)__________

Circumstances

—(9)________:moreobjectiveobservations (9)__________

C:Waystorecordbehaviour(10)________ (10)__________

—observationwithintervention

—participantobservation:researchersasobserverand(11)________ (11)__________

—fieldexperiment:researcher(12)________overconditions (12)__________

—observationwithoutintervention

—purpose:describingbehaviour(13)________ (13)__________

—(14)________:nointervention (14)__________

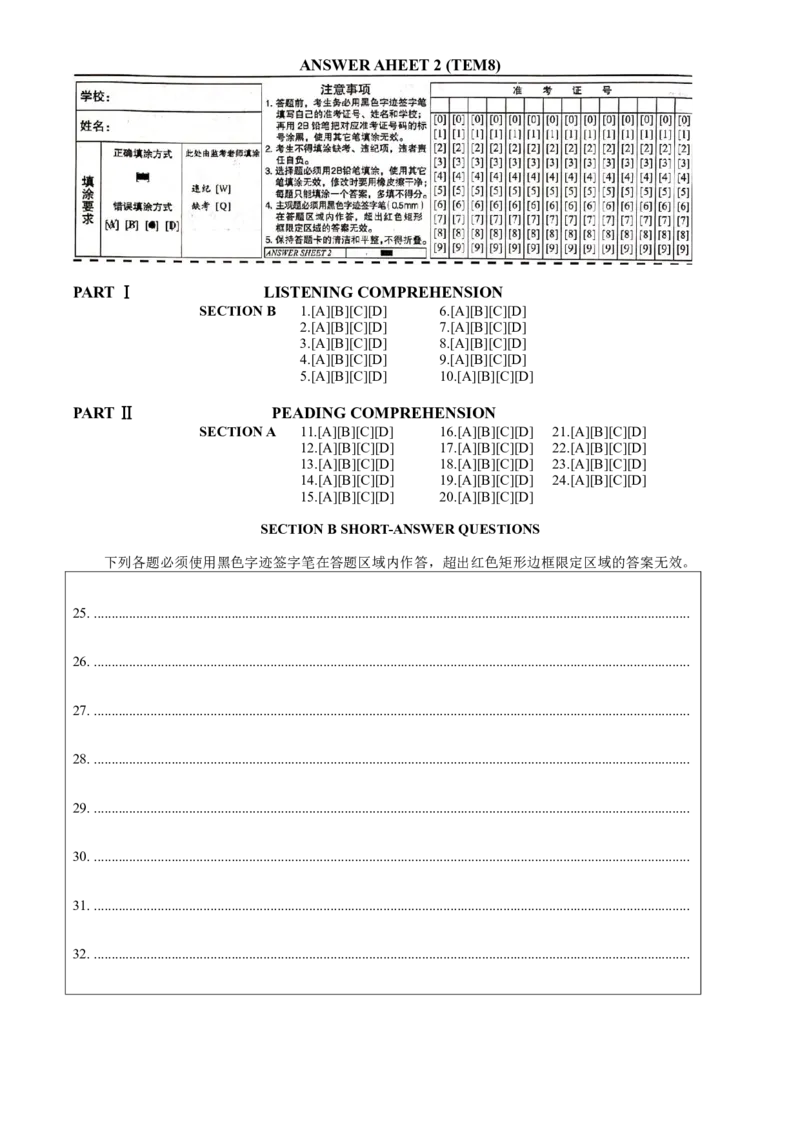

—researcher:a(15)________recorder (15)__________ANSWERAHEET2(TEM8)

PARTⅠ LISTENINGCOMPREHENSION

SECTIONB 1.[A][B][C][D] 6.[A][B][C][D]

2.[A][B][C][D] 7.[A][B][C][D]

3.[A][B][C][D] 8.[A][B][C][D]

4.[A][B][C][D] 9.[A][B][C][D]

5.[A][B][C][D] 10.[A][B][C][D]

PARTⅡ PEADING COMPREHENSION

SECTIONA 11.[A][B][C][D] 16.[A][B][C][D] 21.[A][B][C][D]

12.[A][B][C][D] 17.[A][B][C][D] 22.[A][B][C][D]

13.[A][B][C][D] 18.[A][B][C][D] 23.[A][B][C][D]

14.[A][B][C][D] 19.[A][B][C][D] 24.[A][B][C][D]

15.[A][B][C][D] 20.[A][B][C][D]

SECTIONBSHORT-ANSWERQUESTIONS

下列各题必须使用黑色字迹签字笔在答题区域内作答,超出红色矩形边框限定区域的答案无效。

25..........................................................................................................................................................................

26..........................................................................................................................................................................

27..........................................................................................................................................................................

28..........................................................................................................................................................................

29..........................................................................................................................................................................

30..........................................................................................................................................................................

31..........................................................................................................................................................................

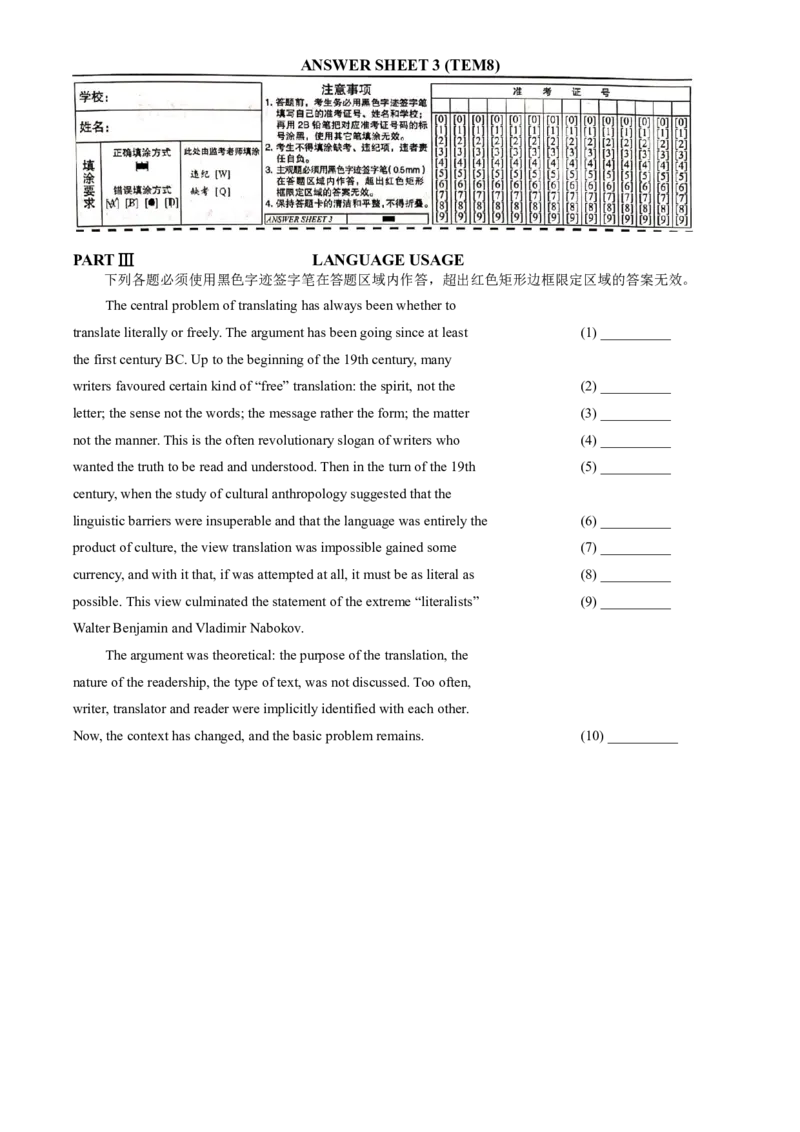

32..........................................................................................................................................................................ANSWERSHEET3(TEM8)

PARTⅢ LANGUAGE USAGE

下列各题必须使用黑色字迹签字笔在答题区域内作答,超出红色矩形边框限定区域的答案无效。

Thecentralproblemoftranslatinghasalwaysbeenwhetherto

translateliterallyorfreely.Theargumenthasbeengoingsinceatleast (1)__________

thefirstcenturyBC.Uptothebeginningofthe19thcentury,many

writersfavouredcertainkindof“free”translation:thespirit,notthe (2)__________

letter;thesensenotthewords;themessagerathertheform;thematter (3)__________

notthemanner.Thisistheoftenrevolutionarysloganofwriterswho (4)__________

wantedthetruthtobereadandunderstood.Thenintheturnofthe19th (5)__________

century,whenthestudyofculturalanthropologysuggestedthatthe

linguisticbarrierswereinsuperableandthatthelanguagewasentirelythe (6)__________

productofculture,theviewtranslationwasimpossiblegainedsome (7)__________

currency,andwithitthat,ifwasattemptedatall,itmustbeasliteralas (8)__________

possible.Thisviewculminatedthestatementoftheextreme“literalists” (9)__________

WalterBenjaminandVladimirNabokov.

Theargumentwastheoretical:thepurposeofthetranslation,the

natureofthereadership,thetypeoftext,wasnotdiscussed.Toooften,

writer,translatorandreaderwereimplicitlyidentifiedwitheachother.

Now,thecontexthaschanged,andthebasicproblemremains. (10)__________